Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories—and some on his friends, too.

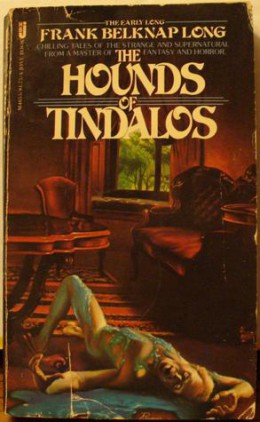

Today we’re looking at Frank Belknap Long’s “The Hounds of Tindalos,” first published in the March 1929 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“No words in our language can describe them!” He spoke in a hoarse whisper. “They are symbolized vaguely in the myth of the Fall, and in an obscene form which is occasionally found engraved on ancient tablets. The Greeks had a name for them, which veiled their essential foulness. The tree, the snake and the apple—these are the vague symbols of a most awful mystery.”

Summary: Our narrator, Frank, visits his friend Halpin Chalmers, author and occultist. Chalmers has “the soul of a medieval ascetic,” but reveres Einstein as “a priest of transcendental mathematics.” His wild theories about time and space strike Frank as “theosophical rubbish.” For example, time is an illusion, our “imperfect perception of a new dimension of space.” All that ever was exists now; all that will ever be already exists. Every human is linked with all life that’s preceded him, separated from his ancestors only by time’s illusion.

Chalmers has acquired a drug which he claims Lao Tze used to envision Tao. He means to combine those occult perceptions with his own mathematical knowledge, to travel back in time. Frank is against his friend taking the “liao,” but agrees to guard him and to note what he says under its influence.

The clock on the mantel stops just before Chalmers swallows the liao, which he takes as a sign that the forces of time approve. Things grown dim around him. He stares at—through—the opposite wall, then shrieks that he sees “everything…all the billions of lives that preceded me.” Parading before his enhanced consciousness are migrations from Atlantis and Lemuria, Neandertalers ranging “obscenely” over Europe, the birth of Hellenic culture, the glories and orgies of Rome. He meets Dante and Beatrice, watches Shakespeare with Elizabethan groundlings, is a priest of Isis before whom Pharaoh trembles and Simon Magus kneels. All this simultaneously, mind you. By straining through what he perceives as curved time, he travels back to the dinosaurs and further, to the first microscopic stirrings of terrestrial life. But now angles multiply around him—angular time, an “abyss of being which man has never fathomed.”

Though this angular abyss terrifies Chalmers, he ventures in. Bad move: He screams that things have scented him, and falls to the floor moaning. When Frank tries to shake him from his vision, he slobbers and snaps like a dog. More shaking and whiskey revive Chalmers enough to admit he went too far in time. A terrible deed was done at the beginning, he explains. Its seeds move “through angles in the dim recesses of time,” hungry and athirst. They are the Hounds of Tindalos, in whom all the universe’s foulness is concentrated. It expresses itself through angles, the pure through curves, and the pure part of man descends from a curve, literally.

Frank’s had enough. He leaves, but returns the next day in response to Chalmers’ frantic call for help and plaster of Paris. Chalmers has cleared all furniture from his apartment. Now they must obliterate all angles in the room, making it resemble the inside of a sphere. That should keep out the Hounds, which can only pass through angles. When they finish, Chalmers says he knows Frank thinks him insane, but that’s because Frank only has a superlative intellect, while Chalmers has a superhuman one.

Convinced poor Chalmers is a “hopeless maniac,” Frank leaves.

Next day the Partridgeville Gazette runs two strange stories. First, an earthquake shook the town around 2 a.m. Second, a neighbor smelled a terrible stink coming from Chalmers’ apartment and found him dead, with his severed head propped on his chest. There’s no blood, only blue ichor or pus. Recently applied plaster had fallen from the walls and ceiling, shaken loose by the earthquake, and someone grouped the fragments into a perfect triangle around the corpse.

Also found are sheets of paper covered with geometric designs and a scrawled last epistle. Chalmers wrote of a shock shattering his curved barriers, and they are breaking through. Smoke pours from the corners of the room. Last scrawl of all: “Their tongues—ahhhh—”

Police suspect Chalmers was poisoned. They send specimens of the blue ichor for analysis. The chemist’s awed verdict is that it’s a sort of protoplasm, alive, but containing none of the enzymes that drive known life and cause its eventual dissolution. In other words, the stuff’s utterly alien and immortal!

The story ends with an excerpt from Chalmers’ book, The Secret Watchers: What if, parallel to our life, there’s life that doesn’t die? What if it can pass from unknown dimensions into our world? Chalmers has talked with the Doels, and he’s dreamt of their maker which moves through strange curves and outrageous angles. Someday, perhaps, he will meet that maker face to face.

What’s Cyclopean: Not nearly enough. Though probably cyclopean masonry would provide all too many angles through which Hounds could enter.

The Degenerate Dutch: In spite of the “black dwarfs overwhelming Asia,” Long sort of gets that different human cultures make important contributions to the species… alas that this plays out most notably in a grab-and-run use of the Tao to explain time travel. The Tao that can be understood as essentially equivalent to the TARDIS is not the true Tao.

Mythos Making: The Hounds of Tindalos get a shout-out in “Whisperer in Darkness,” as do doels—Chalmers might really have managed better with some extraterrestrial guidance.

Libronomicon: Chalmers may be a jerk, but he has quite the library: Einstein, John Dee, Plotinus, Emanuel Moscopulus, Aquinas, and Frenicle de Bessy. Also, presumably, an author’s copy of The Secret Watchers.

Madness Takes Its Toll: As Chalmers gets more desperate in his attempts to avoid all angles, our narrator fears for his own sanity. Chalmers’ efforts with plaster may actually be somewhat sensible, but his claims of superhuman intellect and overconfidence in his auto-experimental studies suggest NPD.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m picky about Lovecraftiana. So very, very picky. And I regret to report that the story in which Long unveils his most memorable contribution to the Mythos is not, itself, terribly memorable.

The Hounds have caught (and presumably mangled) the imagination of many since this first appearance. In my mind, shaped as much by “Witch House” as by their actual description, the hounds are a mass of incomprehensible shapes, hastily scribbled colors and angles visible only in the corner of one’s eye, the suggestion of canine form merely the brain’s desperate final attempt at pattern-matching.

The inescapable hunter is one of horror’s perfect ideas. The wild hunt, the black dog, the langolier… you’ve violated a rule, perhaps seemingly trivial, perhaps inadvertent–and now nothing can keep you safe. They’re coming. They have your scent. They can take their time… and you can shiver under the covers with your book, and try not to notice the things that hover in the corner of vision.

The Hounds add one delicious detail that’s very nearly worth its absurdity in context. As written, the contrast between good curves and evil angles produces eye-rolls. It’s a facile attempt to force cosmic horror into a comfortably dualistic model, with a dash of the Fall of Man to increase familiarity. So much bleah. (Picky. Did I mention I’m picky?) But the vulnerability of angles more intriguing. If you avoid angles, you can escape—but how could you possibly do that? (Chalmers’s solution lacks sustainability.) Angles are rarely found in nature—but they’re a commonplace of human architecture. It’s civilization that gives the Hounds a thousand ways in, through every window pane and cornerstone and altar.

Still, the dualism chafes. It’s made worse by the supposed connection between Chalmers’s inane occultism and the Tao. I guess “Eastern mystics” weren’t so vulnerable to the dangers of mental time travel? Or do people just not notice when they get eaten? Using a veneer of eastern philosophy to prop up your pseudoscience is not only distasteful to modern readers, but boring. I’m pretty sure it was boring in 1930, too, or the story would be well-remembered along with the truly excellent monster at which it manages to hint.

Chalmers doesn’t help the story’s memorability. He’s a blowhard and a self-satisfied jerk—not really a fun person to spend half an hour listening to. He’s the guy who corners you at parties and tells you how clever and contrarian he is. It’s kind of a relief when he gets eaten, except that even at the last he manages to detract from the drama. Exactly no one in the history of ever, set upon by a feared enemy, has taken the time to write: “Aaaaaaahhhhh!”

So the Hounds are awesome, but the story tamps down cosmic horror into convenient human-sized categories. One illustration: Long’s narrator dismisses modern biological explanations for human origin, where Lovecraft would simply tell you that evolution is terrifying, implying as it must the impermanence of species and form.

One of my favorite bits of “Hounds” is the overview of human history, which covers a far wider range of civilizations and textures than Lovecraft ever manages. There’s a beautiful paragraph, nearly worth all the flaws, where Chalmers sees a galley ship simultaneously from the perspective of master and slave. Lovecraft wouldn’t, couldn’t have written that—but he’d fill the gaps with Yith and Mi-Go, Elder Things, hints of life on Neptune and pre-human invasions. Long understands human history better, but his world is humans all the way down, right up until you get to the primal break between foul and fair. His cosmic vista lacks scope.

Can’t we have both?

Anne’s Commentary

Frank Belknap Long was one of Lovecraft’s inner circle, and his “Hounds” is the first Mythos tale which Lovecraft neither wrote himself nor collaborated on. Perfect start for our consideration of the extra-Lovecraftian Mythos, that slow but unkillable creep of cosmic terror into other susceptible minds! Long would go on to create Great Old One Chaugnar Faugn and to kill a fictionalized Lovecraft in “The Space-Eaters.” But the Hounds are probably his most famous creation. Lovecraft mentions them in “Whisperer in Darkness.” Writers as diverse as Brian Lumley, Roger Zelazny, Sarah Monette and Elizabeth Bear, William S. Burroughs, and John Ajvide Lindqvist have evoked them. They also haunt video and roleplaying games, metal songs, anime, illustration. Well, why shouldn’t the Hounds be pervasive? Have angles, they’ll travel, lean and athirst.

“Hounds” has always inflicted shivers on me. This reread, I was momentarily distracted by a few infelicities. The story strikes me as way too short for its expansive subject: all of time and space and the wonders and horrors therein. Info-dumping through conversation is ever tricky, especially when “said” succumbs to a flood of dialogue tags like “murmured reverently,” “affirmed,” “retorted,” “murmured” again, “murmured” again, “admonished,” and “murmured” again, twice in quick succession. Later we get a spate of “shrieks” and “cries” and “moans,” followed by yet more “murmurs” and “mutters.” Less quibbly on my part, perhaps, is a time discrepancy (everything seems to happen over 2-3 days, yet the newspaper notes that Chalmers moved his furniture out a fortnight ago.) And why does Frank disappear from part three, except as implied collector of clippings and excerpts? Could be both Franks (author and authorial stand-in) wanted to let the aftermath speak for itself. Could be author Frank counted up his words and felt a need to truncate.

It’s not that part three falls apart or ruins the tale. But I would have liked to see Chalmers get Frank back to his apartment for the climax. That would eliminate the need for those bad-trope scrawls in the margins of Chalmers’ diagrams. Frank could have witnessed what Chalmers had to (improbably) record: The plaster falling, the Hounds smoking in, the tongues. Nor would we have to suffer that handwritten last wail of despair, “ahhhh.” Doubtless followed by a frantic skid of the pen across the page. Now if Chalmers had audio-recorded his observations, a la “Whisperer in Darkness,” the “ahhhh” would be okay. But who takes time to write out a scream? Then again, poor Chalmers was a medievalist at heart, so wasn’t likely to own a recorder.

Finally, Long seems to realize that Chalmers had better disrobe while he sits vigil against the coming of the Hounds. Clothes do have angles, especially if you’re wearing early-20th-century collars and crisp cuffs. However, he lets Chalmers keep sheets of paper in the sphere-room, bearing writing and diagrams, which presumably have angles in them. At least we don’t hear that Chalmers rounded the corners of the sheets, or that the diagrams are all curvilinear.

It would have been cool if the Hounds came through the papers! Instead they just provide another quibble.

Enough. There are compensating felicities. I like the idea of combining an alchemical drug with mathematical study to travel through time. I salute the attempt, not altogether vain, to bring Tao into the Mythos. That great recumbent body containing the universe, that monster seen through the slit of our limited perceptions, the havoc wrought by seeing the beast whole. I enjoy Chalmers’ jaunt through his previous identities, for what he chooses to mention out of the vast, simultaneous panoply is highly characterizing. He’s obviously a scholar of the classical world and of European literature, for he dwells on Greece and Rome and brags about hanging with Dante and viewing Merchant of Venice fresh from Shakespeare’s pen. He might have been a slave on a Moorish galley and a victim of Nero, but he was also a Legionnaire, a Caesar, and a priest of Isis who had Pharaohs and famous magicians at his beck and call. I’m reminded a little of H. G. Wells’ traveler in The Time Machine, though that traveler’s journeys are far more sweeping and moving, especially his last one forward to the terrible red end of the world.

And the Hounds! The lean and hungry and thirsty and stinking and blue-ichor dripping Hounds! How they wander through outrageous angles, epitomes of what we would call evil, what Chalmers qualifies to foulness. They are the seed—the children—of some monstrous deed, a fall from grace symbolized but feebly in our Bible by the expulsion from Eden, with its tree and snake and apple. Who or what could have committed the deed? Why? How? Tongues, too. Or rather, tongues. That’s the only detail Chalmers has time to note about the physiognomy of the Hounds. Not the Hounds’ eyes, or scenting noses, or even teeth. Their tongues!

Nice one. Big points for evocative spareness and imagination-triggering. But can I still wish Frank had been present to see more, and had lived to tell us?

And what about that blue ichor, which turns out to be an enzyme-free protoplasm that can live forever? From his report, the chemist and bacteriologist James Morton knows he’s got something big there, so is he going to dump that ichor sample down the drain? I bet he’s keeping it. Maybe sharing it with scientists at Miskatonic University, if Long’s fictional Partridgeville is anywhere near MU. One of the characteristics of life is growth. Another is self-perpetuation.

Oh yeah. There are enough story bunnies in the blue ichor to stuff a Cyclopean hutch. Does anyone know if any blue and slimy rabbits have escaped into the Mythos wild yet?

Next week, in “From Beyond,” Lovecraft proves there’s more than one way to expand consciousness beyond the fragile soap bubble of ordinary human perception—and more than one reason why it’s a bad idea.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.